SITE IN SPANISH

I wanted to write this blog post, first, to explain how the focus of our project on affective and immaterial labour in Latin(x) American culture emerged and, second, to introduce the research into cultural portrayals of sex work that I have recently begun. I realise that it might seem unusual that our project explores representations of such different types of labour (wet nursing, migrant domestic work and sex work) and spans such a lengthy period (from the late nineteenth century to the present day), but my sense that links – which traverse historical eras and types of media – were being drawn between these forms of work surfaced as I was writing my last book, Paid to Care: Domestic Workers in Contemporary Latin American Culture. I noticed that lots of the texts I was analysing were drawing connections – both critical ones and problematic ones – between domestic work and other forms of waged or unwaged reproductive labour, such as sex work, breastfeeding and child-rearing.

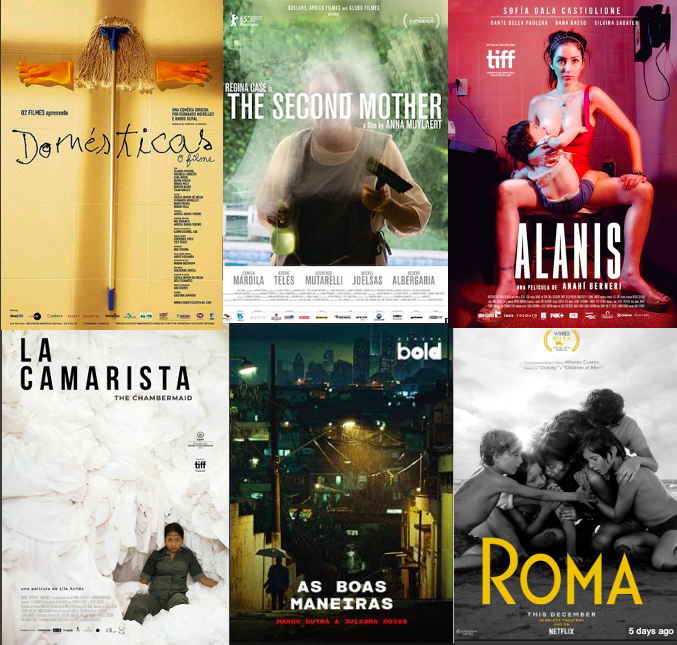

The two films I’ll focus on here, which explore the experiences of sex workers – Alanis (Anahí Berneri, Argentina, 2017) and Patrícia (Alexandre Carlomagno, Brazil, 2014) – are characteristic of a recent trend in Latin American cinema to link different forms of gendered, reproductive labour together. Other examples include Consuelo Lins’ short documentary Babás (2010), which locates the roots of contemporary childcare arrangements in Brazil in the historical practice of wet nursing that was enabled by enslavement, and Lila Avilés’ film La camarista (2018), which focuses on a hotel cleaner, Eve, and skewers gendered expectations by exploring the ways that its protagonist is compelled into performing informal childcare duties for a guest and coerced into serving as a figure of sexual release for one of the hotel’s window cleaners.

These links were already being identified in the 1970s and 1980s by Italian feminist theorists such as Silvia Federici and Leopoldina Fortunati who observed that capitalist economies rely on the separation of reproductive labour, or the work involved in the reproduction of the workforce – such as domestic work and sex work – from productive labour (Fortunati 1995, 7). While Federici focuses on the naturalisation of the unpaid domestic labour that women do at home, arguing that capital ‘makes money’ out of women’s cooking, smiling, cleaning and fucking (2012: 20-21), paid domestic workers also suffer from the conflation of different forms of reproductive labour and the ways these are engendered and often racialised in Latin America. Valeria Ribeiro Corrosacz’s ethnographic research into white middle-class masculinity in Rio de Janeiro has found that it has been common for men who are members of the dominant class to identify sexual initiation with their family’s domestic worker as a kind of rite of passage (2017, xii-xiv, 49-50). The gender, race and class status of paid domestic workers has made male members of employer-families feel that they are entitled to domestic workers’ bodies.

Despite their important differences, domestic work and sex work are often characterised by workers’ experiences of vulnerability, precarity, informality and intimacy. The fact that domestic workers and sex workers, as well as other kinds of care workers, come into close contact with other people’s bodies and bodily fluids has made it possible to associate their work with dirt or waste, and thus with the abject. These connotations have sometimes wrongly led to these workers’ stigmatisation. This process is intensified in the case of sex work, where close physical intimacy is part of the job and where there are health-related concerns, particularly regarding sexually transmitted infections. Fears surrounding the defilement of women’s bodies through sex work have been deployed in Latin American works as a metaphor for the corrosive effects of modernity (Wells 2019, 224), including the plundering of the natural world, such as in the Brazilian film Iracema: uma transa amazônica (Jorge Bodanzky & Orlando Senna, 1974). These works are often interested in depicting sexual exploitation or sex trafficking, sometimes of minors. Alanis and Patrícia do not employ this metaphor and I think this is because their principal objective is to advocate for and frame sex work as work, as well as to depict sex workers’ potential for agency.

Alanis is a fiction film that depicts two days in the life of its eponymous protagonist who is a sex worker living in Buenos Aires. At its opening, Alanis and her friend Gissela are evicted from their apartment by the police. Gissela is arrested and treated as though she is Alanis’ handler. Following this, the film portrays Alanis’ struggles to continue working while caring for her 18-month-old son, Dante, without Gissela’s support. The film is motivated by a desire to explore the current legal conjuncture faced by sex workers in Argentina. The country has adopted an abolitionist approach, which means that it is third parties that exploit the prostitution of others that are criminalised, rather than sex work itself (Orellano 2016). In reality, the distinction between a prohibitionist and an abolitionist approach is blurry. Since 2011, a powerful anti-trafficking lobby in the country helped to bring in new laws that do not differentiate human trafficking from sex work (Orellano 2016).

Patrícia is an interview-based Brazilian documentary that is available in full on YouTube (without English subtitles). The film paints a multi-layered portrait of its sex worker protagonist, who reflects on her job, her childhood, and her enjoyment of Shakespeare, among other topics. Patrícia describes herself as ‘kind of an activist’, and the documentary enables her to speak about her work supporting others in her industry, including through her involvement in the NGO Vitória-Régia, of which she was president for a time. She explains that she has helped to organise workshops that train health workers in how best to respond to the requirements of different kinds of sex workers, for example.

The films are united by their explorations of sex work and its affective and performative dimensions. They link sex work to other types of reproductive and affective labour. I am defining affective (or immaterial) labour here as embodied forms of work that nonetheless include the production of feelings, emotions, relationships or information as key outputs. In Alanis, these forms of work include domestic labour, care work and child rearing. In Patrícia, they include waste collection and the protagonist’s activism, which has the objective of promoting and protecting the health and well-being of other sex workers. The films’ emphases on the production of affect through different forms of reproductive labour, together with their affective appeal to spectators, enable them to align the experiences of sex workers with those of many other kinds of workers in capitalist economies on the level of their immateriality and precarity – an argument also made by Sarah Ann Wells (2019, 222). In so doing these films are, most importantly, advocating for sex work to be treated as another form of work.

Whenever she is not attending clients, Alanis is shown feeding and caring for her son. In one scene, Alanis reclines on the bed, where she later expects to receive a client so that Dante can nurse. In the background, a lacy red cloth draped over the bedside lamp functions as an allusion to Alanis’ employment.

Marina Gamba argues that this scene makes reference both to Renaissance depictions of the Madonna and of nudes, such as the Venus of Urbino (Titian, 1534) (2021, 95). The film thus signals the underlying links between two ‘prototypical visions of feminine corporeality’ – the Madonna and the whore – that are usually presented in opposition (Gamba 2021, 95). Alanis is also the protagonist’s professional name, while her given name is María, signalling even more overtly how she embodies both identities. Later, Alanis attends a regular client who sucks her nipple as Alanis’ face is shown in profile, like in the sequence that previously showed her breastfeeding. In both scenes, Alanis appears distracted, but her expressions communicate distinct affects. While Alanis’ strong emotional attachment to her son is foregrounded throughout the film, her interactions with clients, although intimate, are usually marked by a certain distance or detachment that signal the fact she is providing a service in return for payment or, in other words, that she is working.

Alanis nonetheless expresses a preference for sex work over alternative types of employment. After she and Gissela are evicted, Alanis is forced to seek refuge for herself and Dante with a friend who openly disapproves of Alanis’ usual work and arranges a position for her in the home of a woman who has a disability and needs someone to clean for her. The sequence in which Alanis is shown cleaning the woman’s bathroom underscores the negative affects Alanis experiences while undertaking this labour. As she scours the toilet, we see disgust in her expression, but when she stands up to scrub the sink, the camera remains static, cutting her face out of the frame and leaving the audience to project their own feelings on to her as she removes hair from the plughole. Alanis never returns to work in the woman’s home. Instead, she sneaks out at night to do sex work. Her narrative reminds spectators that “for most women sex work is not the only option for making a living” (Gerasimov 2018). For some, it is preferable to lower-paid jobs such as domestic work.

Carlomagno’s documentary explores these issues even more explicitly via the interviews with Patrícia who comments that it pleases her that clients pay well for what she offers. She enjoys describing the emotional and psychological elements of her interactions with customers and talks about how she has a particular strategy that includes showing affection. She states that she is the one who calls the shots in these interactions, which empowers her.

The interviews in which both protagonists participate in these films signal most strongly their refusal to serve as figures of negative social affect and to conform to the role of victim that others attempt to ascribe to them. Alanis’ pivotal scene involves the protagonist being questioned by the police.

It quickly becomes clear that the interview is designed to paint her as a victim of trafficking. Alanis states that she was 23 when she willingly came to Buenos Aires from her hometown of Cipoletti (Río Negro). The interviewer nonetheless presses her to go into greater detail about her relationship to Gissela. Alanis explains that they share the rent and bills in their apartment, Gissela also attends clients and she is her friend. Alanis begins to play on the interviewer’s prejudices when he asks her about her son’s birth by joking that Dante was born at home when her waters broke while a client was having sex with her. Immediately afterwards, she laughs and reveals he was actually born in hospital.

Alanis’ story is designed to illustrate the negative consequences of anti-trafficking laws that frequently result in sex workers being arrested and treated as victims of trafficking (Garofalo Geymonat and Macioti 2016; Blanchette and Murray 2016). Sex workers organisations have repeatedly pointed out that “in practice, ‘saving prostitutes’ means taking away their livelihoods” (Garofalo Geymonat and Macioti 2016). Alanis’ eviction from her apartment not only takes away her income but also compels her into hostile environments. She is forced to walk the street to find clients and is physically attacked by other sex workers for invading their territory.

Just like Alanis, Patrícia also makes the audience aware of their own fascination with the sex worker’s image. Its opening and closing sequences show Patricia walking along the street, thereby placing the spectator in the same viewing position as a prospective client. Both Patrícia and Alanis deploy dirty or scratched mirrors to signal that the audience’s understanding of the sex workers’ experiences is mediated and incomplete.

These distancing devices are important in a documentary like Patrícia which uses an investigative interview to explore and depict the experiences of a real sex worker via a method that echoes forms of ethnographic research. Nicholas De Villiers has highlighted the parallels between ethnography and pornography as methods for finding out more about an issue that is unknown to the researcher or viewing a practice that is usually carried out privately (2017, 2). He terms documentaries about sex work that feature interviews “confession porn” and foregrounds the power relationship between the filmmaker and the sex worker (De Villiers 2017, 10).

In places, there appears to be an assumption that Patrícia will function as a kind of confessional. Occasionally, the camera continues to roll for some moments after Patrícia has signalled that she no longer wants to speak. The affective labour expected of her ironically recalls Patrícia’s description of the emotional elements of her interactions with clients, with the important distinction that the latter, as she describes them, are often enjoyable. What is significant here is the choice to signal that Patrícia exerted a certain level of influence over her portrayal in the documentary and negotiated what she would and would not disclose about herself. When talking about her childhood and the sexual violence she has suffered, she often becomes emotional and chooses not to continue. She either asks for a break or visualises cutting by making a signal with her hands or picking up a pair of scissors, and the filming is stopped. At various points, Patrícia also tries to engage members of the crew in conversation. Her behaviour indicates a refusal to act as the camera’s passive object, and her subjectivity and sense of humour emerge as she attempts to establish a dialogue. As well as commenting on the advantages and disadvantages of her work, Patrícia expresses her love for her dog, who she goads into pleasuring itself on her leg because, she says, finds it funny.

Patrícia’s approach, like the approach of the film Alanis as a whole, is playful and provocative. Both films, I argue, can be understood as forms of “puta politics”, which Laura Murray describes as mixing “calculated political strategy with playful and provocative protest” (Blanchette and Murray 2016). Inspired by Brazilian sex worker activist, Gabriela Leite, and her political use of the word puta (whore), Murray defines puta politics as the strategic leveraging of aspects of the puta subjectivity to: “mobilise allies, media attention and state power in favour of prostitute rights. Puta politics refuses victimisation, invests in the transformative potential of what is often perceived of as immoral, and disrupts divisions between institutional structures and the street” (Blanchette and Murray 2016).

Rachel Randall is Senior Lecturer in Latin American Cultural Studies at the University of Bristol. Her research explores representations of reproductive and affective labour and childhood and adolescence in contemporary Latin American film in particular. She has just completed a book entitled Paid to Care, which examines the depiction of paid domestic workers in post-dictatorship Latin American cultural production, including in film, documentary, literary testimony (testimonio) and digital culture. The book will be published by the University of Texas Press in 2023.