By Andrea Aramburú Villavisencio, Daniela Meneses Sala and Rachel Randall

On 25 May 2023, we organised a workshop for postgraduate and early career researchers in Bristol: “Creative Visual Methodologies: Affective Interventions in Archival Materials”. The idea was to experiment with the affordances of creative and caring methodologies when exploring archival materials that both reveal and conceal forms of affective labour. Participants in the workshop were confronted with a series of photographs featuring wet nurses and infants that were taken in Lima in the nineteenth century. The product of their interventions into these photographs is this zine.

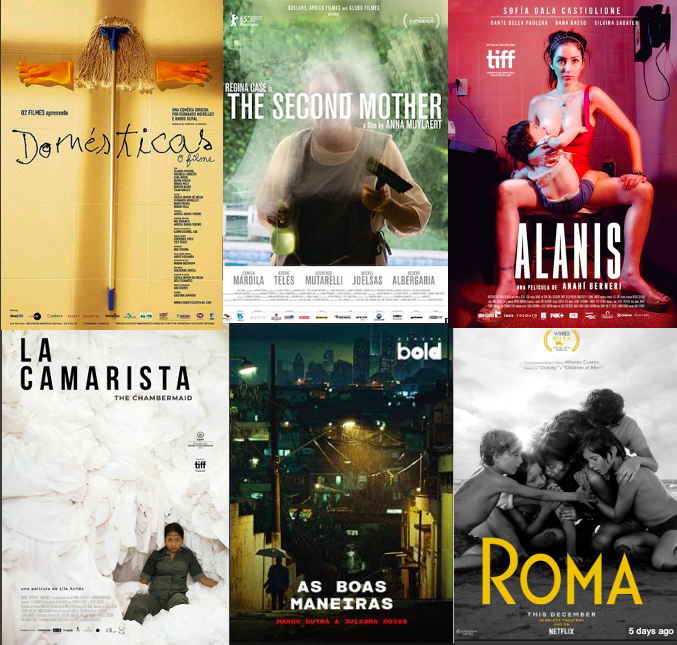

The zine features a series of reappropriations and critical reworkings, via collage techniques, of a set of photographs from the Courret Archive at the Biblioteca Nacional del Perú (BNP).

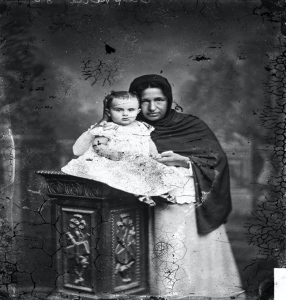

The archive, now fully digitised, is made up of thousands of glass plates originally from Fotografía Central, a photography studio founded in Lima in 1863 by the French brothers Eugène and Achilles Courret. In nineteenth-century Peru, the Courret brothers were key figures involved in one of the crucial technologies of “mechanical reproduction” conceived to construct the bourgeois, modern image of the nation and its citizens: photography. Through the lens of Eugène Courret, we saw the Creole elite of a Lima in which independence was still nascent. Even if society’s marginal citizens were not the focus of Courret’s photographs, they still appear in many of his portraits, often as secondary characters. His representations, as such, contributed to the creation of stereotypes, often reinforcing differences of class and race. This is the case of a series of images scattered within the archive, where children appear held by their wet nurse or nanny, a role which at the time was popular amongst Lima’s elite family and which was commonly taken up by Afro-Peruvian women. In some of these photographs, these women appear covered with drapes or partially concealed; in others, they look directly at the camera as they hold their charges close to their chests; and in some, which are meant to feature newborns on their own, the wet nurses are almost entirely erased from the frame, though occasionally they leave behind a trace for the careful observer, like a hand or the glimpse of a head.

Our first encounter with these images provoked a series of questions related to how archives articulate remembrance, how they perpetuate (and yet invisibilise) the violent structural conditions sustaining the historical moments they memorialise. Society’s marginalised actors are anonymised, violently hidden and ignored, even if the archive retains their presence in plain sight. It was in this context that we came up with the idea of making an art workshop. Inspired by the works of scholars such as Saidiya Hartman, our aim was to recuperate, in a caring manner, the centrality of the wet nurse figure in the Courret Archive. By “caring”, we refer to a critical engagement encompassing the complexity of this task, the fact that we may often be required to sit with discomfort and the conscious recognition that each of the women who appear in the photographs were subjects with a life and a history of their own. We wanted to create a counter-archive that would bring attention to these women, their care work and the structures behind their oppression, both within and beyond the archive.

We prompted our participants to critically reflect on, even play with, the photographs’ materialities, cutting them up, juxtaposing them, finding associations with quotations and other visual objects. Part of our objective was to produce a collective and thoughtful response to the archive, one that could consider the various forms by which material, active interventions could bring the often invisibilised labour of care work to the fore.

The pages that the workshop participants and facilitators created compose the zine. The thought-provoking interventions reflect individual and collective concerns as well as the participants’ varied disciplinary backgrounds. Many interventions self-reflexively foreground the limits of the participants’ understanding. Tropes such as the inclusion of reflective paper or a polaroid photograph enable participants to meditate on their positionality or to foreground the limitations of indexical materials (such as celluloid photographs) in providing historical insight. A second trope that resonates across the zine is the irreverent swapping of roles and positions, including the gesture of bringing the wet nurses to the centre, which often requires the babies to be relegated to the background or even disappear from the pages. We see, for example, pages where wet nurses are shown holding each other or where they appear in groups, as well as a page where a wet nurse’s head is attached to the body of an infant, and the wet nurse is almost engulfed by the veiled figure of a baby behind her. These interventions draw attention to the ambivalent nature of care work and to the race, class and gender identities of those who provided it and continue to provide it today. Finally, many of the pages play on the visible signs of wear and tear in the photographs and the presence of the archival watermark, which are deployed as indictments both of violent archival practices and of the suffering that the role of wet nurse could have entailed for some of the women pictured.

The digital form in which we have made this zine available both adds to and takes away from the original, hand-made pages created at the workshop. The latter are characterised by participants’ uses of mirror paper, flaps that can be opened and closed and interventions that extended beyond the edges and on to the reverse of the pieces of card provided.

We have done our best to do justice to participants’ thoughtful and creative interventions when compiling this zine, and we hope that interacting with it is an engaging experience for you as a reader. The zine will soon be printed using risography, and we will add photographs of the physical version to the zine page on this website as soon as possible.